Opinion: Papa Wojtyla as Capeman Romans have seen so many Popes that they often refer to them by their family names. Capeman refers to what the sculpture, in fact, looks like. First Published in The I talian Insider newspaper in Rome.

The statue of Pope John Paul II stands in front of Termini Station.

By CORNELIUS SULLIVAN

I did not read the article right away with the headline, Sculpture of Pope John Paul II Slammed, because I thought it was just about another blasphemous piece in a museum like the one of the pope crushed by a meteorite. At least I do not have to go to that particular museum to be insulted by it but I will go by the train station many times and will be forced to see Man with

Maybe the pope as a pin head with the gesture of a flasher was not meant to be blasphemous, but most viewers agree it is ugly. When I say this I do not want to be disrespectful to the pope. It is just that images and gestures do have meanings independent of intentions. If we are not cognizant of what they are, we can be duped.

The Associated Press article of a month ago told of the dislike of the Vatican for the statue because it did not resemble the pope and how many citizens said it looked more like Mussolini.

Let us analyze what the sculptor tried to do. The best that one can say about the work is that it bears a superficial resemblance to Early Modern Italian sculpture and for example, the work of Giocomo Manzu known for his Doors of Death across the river at Saint Peters Basilica. Manzu successfully abstracted figures but he retained their humanity and he could draw.

Because he could draw, his figures have truth and his portraits of Pope John XXIII are recognizable and give us the man. Manzu and his colleagues of the time, like Marino Marrini and others, were so excited to wield form in a free way and reveal properties of the material, the flow of clay, and the reflective sheen of bronze. But they retained the classical discipline of drawing.

It is not as if Blessed John Paul did not give us a super abundance of gestures, gestures from the trained and always appropriate actor. There were so many gestures of blessing, so many gestures of caring and listening. He showed to countless people, and they have testified, that he thought they were all that mattered to him at that moment.

The extended cape to enclose the faithful is dreadful because it means nothing even though it has an anecdotal base. I was once asked to make a sculpture of the Blessed Virgin with children of all different races and colors under her mantle. I said I would not do that. It is not good art because it has no human meaning. A political ideology can never translate so directly into sculptural form. Kitsch hits you over the head with an inane idea. It lacks subtlety. A theologian friend said recently, it is like a used car salesman putting his hand on your knee.

Maurizio Cattelan’s sculpture sold for 3 million dollars

The interesting thing about the blasphemous work of Pope John Paul II being crushed by a meteorite by Maurizio Cattelan, La Nona Ora, 1999, (exhibited at Royal Academy, London, sold at Christies for three million dollars), is that the plastic exact replica of the Pope stooped and falling is indeed how we all saw him die. He showed us how to die as his mentor, Jesus Christ, did. Who knows what his being crushed by the big rock is supposed to mean? It becomes very expensive kitsch because it serves a political point of view.

.jpg)

In a similar way, the famous work of 1987 by Adres Serrano, Piss Christ was made to shock, hence the title. The little crucifix in a jar of urine offended many. Without the title, if you just viewed the photograph, the photograph is the artwork, you would see a crucifix bathed in streaming golden light. Art critic Lucy Lippard writes, it is a darkly beautiful photographic image… the small wood and plastic crucifix becomes virtually monumental as it floats, photographically enlarged, in a deep rosy glow that is both ominous and glorious.” If you did not know the title, you would not be offended. But why did he do it? Why does Serrano throw something in our face and on our belief?

The sculptor flying cape maker has stumbled upon an image that has an ambiguous meaning and at the same time fails the test for interesting Modernist form. You see it once, you got it all. There are no subtleties to discover, do not hope it will get better with time. And to bad it is bronze, that indestructible metal of importance. This piece of sculpture will never acquire the charm and magic of any of the marble talking statues in the city, like the Pasquino. They weather, people write on them, they are like us in the city and do not call attention to themselves with a set apart monumentality, and they do not hit us on the head with a one note message.

I have sited two works of art that were made expressly to offend. With fondness I show two sculptures, the Manzu relief, and the Pasquino, two works that have become part of the integral fabric of the city. They have evolved organically and were not products of the government foisting something not right upon the citizens.

It is not good that artists work alone today. That is the only explanation of how this awkward sculpture could have happened. Would that a peer, a friend, had said early on, Lose the cape it is a bad idea. Artists did not always work in isolation.

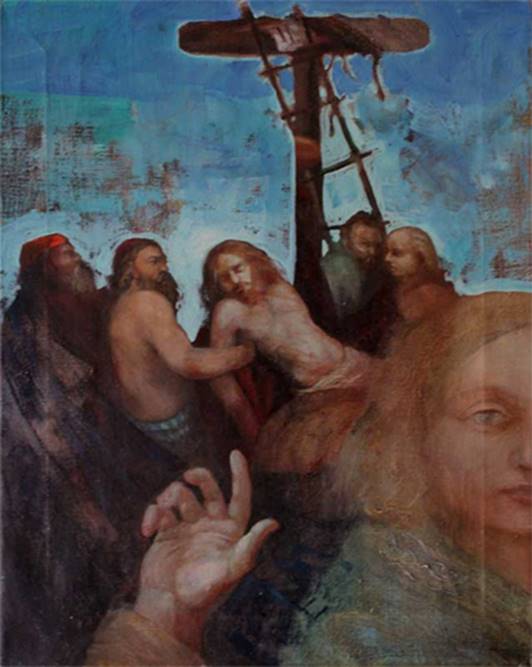

“The most remarkable meeting of Renaissance artists ever recorded, arguably the most extraordinary encounter of its kind in history, occurred on

On the committee were Leonardo da Vinci and Sandro Botticelli. There were no lawyers, no politicians, and no hobbyists. Peer involvement guaranteed quality.

This sculpture of the pope represents the antithesis of the dignity of the individual human person as articulated in Blessed Pope John Paul in his Theology of the Body. From a writer friend, It is pretty awful—it’s Marxist art—the attempt to meld the individual into the collective—and so, it’s ugly because it’s false.