SACRED ART

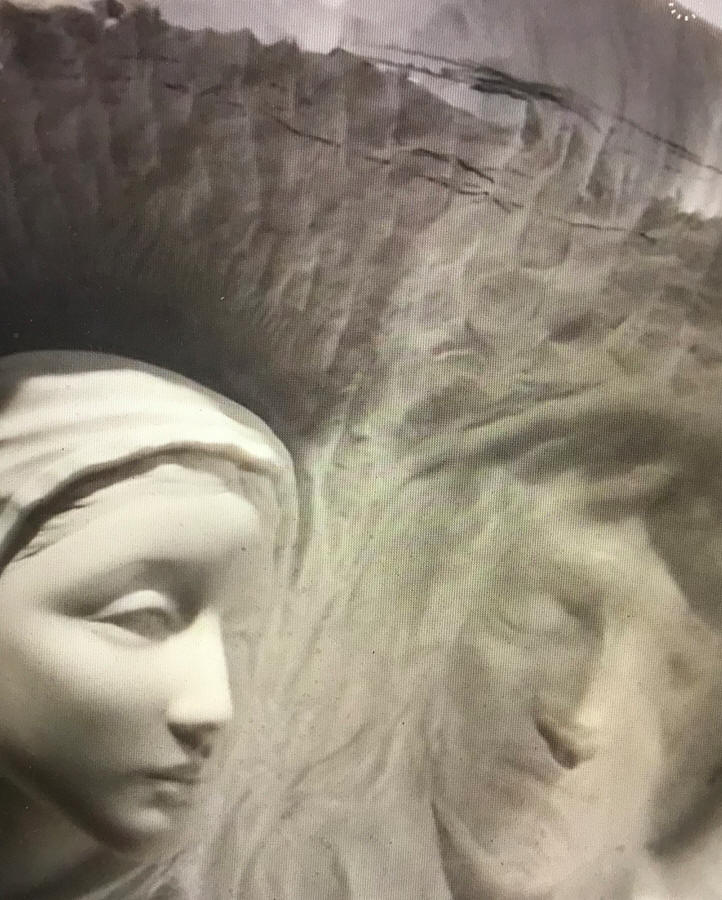

Pieta, Michelangelo, 1499, Saint Peter’s Basilica,

January 20, 2014 revised October 2018

Cornelius Sullivan

Pope Benedict the scholar has not cited the great intellectual tradition of the Church, he names two places where the faith is en-fleshed. These two treasures still inspire pilgrimages. Pilgrims go to

No Catholic university has a Department of Sacred Art. Blessed John Paul II and Pope Benedict have insisted that art should have a major role in the New Evangelization.

With a few exceptions, works of art in Catholic Churches today are ordered from the catalogs of furniture suppliers, the ones who provide the pews and the candle sticks. This is in spite of the clear urging of the Second Vatican Council almost a half a century ago for pastors to use local artists to create religious works.

Hans Urs von Balthasar has said that beauty changes us and that,

“We no longer dare to believe in beauty and we make of it a mere appearance in order the more easily to dispose of it. Our situation today shows that beauty demands for itself at least as much courage and decision as do truth and goodness, and she will not allow herself to be separated and banned from her two sisters without taking them along with herself in an act of mysterious vengeance. We can be sure that whoever sneers at her name as if she were the ornament of a bourgeois past — whether he admits it or not — can no longer pray and soon will no longer be able to love.” 2.

From the poet author of “The Hound of Heaven”, Francis Thompson:

The Church, which was once the mother of poets no less than saints, during the last two centuries has relinquished to aliens the chief glories of poetry, if the chief glories of holiness she has preserved for her own. The palm and the laurel, Dominic and Dante, sanctity and song, grew together in her soul: she has retained the palm, but forgone the laurel. … But poetry sinned, poetry fell; and in place of lovingly reclaiming her, Catholicism cast her from the door to follow the feet of her pagan seducer. The separation has been ill for poetry; it has not been well for religion. 3.

Catholic colleges and universities have preserved intellectual disciplines from earlier centuries with core classes in Theology, Philosophy, History and the study of Literature, but they have shied away from any creativity in art. Instead they have embraced Reformation like iconoclastic ideas. And art is partly to blame. As Thompson said “poetry sinned”. Art sinned even more. Art became autonomous, no longer serving, but always proclaiming its own newness and freedom from restraint and even freedom from relevance to people’s lives. The self referential stance of Modern Art inevitably had to lead to a complete break with any connection to the real, as most people view it, ending in Conceptual Art, art solely as an idea. So, art has become just an idea that man the creator generates. There is no acknowledgment that he is a creature and there is no realization of the truth of the Incarnation. The Church’s distance from music has not been so great because some consensus has been possible. Bad music hurts the ears. Bad art can be shrugged off and then it lingers somewhere in the back of the brain like a bad dream. The elitism of contemporary art is maintained. Typically American Catholics say, “I don’t know anything about art.” and under their breath mutter, “And I don’t care.”

A particular feature of Catholic art is that it tells of universal truths through the particular. There is no such thing as sacred abstract art. There is no such thing as “Reformation Art”.

Sir Kenneth Clark, the great Protestant art historian understands Catholic art in a profound way. In his classic book Civilization he includes what has been written out of history, the beheading of statues of the Virgin in Reformation England, and at the same time he is able to explain the greatness of Catholic art. He does maintain his biases, for example, in saying that ideas flourish more easily in the North. But he shows his depth of understanding of great art in describing how art is linked with an understanding of the female in religions and with the idea of the particular signifying the transcendent.

He says:

” The great achievements of the Catholic Church lay in harmonizing, humanizing, civilizing the deepest impulses of ordinary, ignorant people. Take the cult of the Virgin. In the early 12th century the Virgin had been the supreme protectress of civilization. She had taught a race of tough and ruthless barbarians the virtues of tenderness and compassion. The great cathedrals of the Middle Ages were her dwelling places upon the earth. In that Renaissance, while remaining the queen of Heaven she became also the human mother in whom everyone could recognize qualities of warmth and love and approachability. Now imagine the feelings of a simple hearted man or woman — a Spanish peasant, an Italian artisan — on hearing that the Northern heretics were insulting the Virgin, desecrating her sanctuaries, pulling down or decapitating her images. He must have felt something deeper than shock and indignation: he must have felt that some part of his whole emotional life was threatened. And he would have been right.” 4.

It is not so difficult to imagine that only the “cult of the Virgin” could civilize the barbarism of our age.

Clark goes on to explain why religions of the will have no art, ” The stabilizing comprehensive religions of the world, the religions which penetrate to every part of a man’s being — in Egypt, India or China — gave the female principle of creation at least as much importance as the male, and wouldn’t have taken seriously a philosophy that failed to include them both. The great religious art of the world is deeply involved with the female principle.” 5.

Pope Benedict XVI has said about the Pieta concept, “The languages into which the Gospel entered when it came to the pagan world did not have such modes of expression. But the image of the pieta, the Mother grieving for her son, became the vivid translation of this word. In her God’s maternal affliction is open to view. In her we can behold it and touch it. She is the compasio of God, displayed in a human being who has let herself be drawn wholly into God’s mystery.” 6.

Pieta 2018, detail, marble, life size, by the Author.

John Saward in his book, The Beauty of Holiness and the Holiness of Beauty, makes a connection between beauty and holiness:

Without the holy images, we are in danger of forgetting the face and thus the flesh of the Son of God. The mysteries of the life of Jesus fade from our minds. In the eight and ninth and sixteenth centuries, and again in our own time, Iconoclasm always tends towards Docetism. Robbed of the beauty of sacred art, the Christian can become blind to the beauty of Divine Revelation. And that is disastrous, for, when sundered from beauty, truth becomes correctness without splendour and goodness a value of no delight. 7.

The holiness of beauty is ordered to the beauty of holiness. Sacred art is intended to encourage saintly life. Both are transparent to Christ, radiate the splendour of His truth. Both, in their different ways, are gifts of God. 8.

1. The Ratzinger Report Messori, 1988.

2. Hans Urs von Balthasar , The Glory of the Lord: A Theological

Aesthetics: Seeing the Form, #1, 1982.

3. Francis Thompson, frontispiece, The Beauty of Holiness and the Holiness

of Beauty, Art, Sanctity & The Truth of Catholicism ,John Saward, Ignatius, 1997.

4. Civilization, Kenneth Clark, Harper & Row, 1969, p. 175

5.

6. Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, Mary, The Church at the Source,1997.

7. Ibid, John Saward, p. 25

8. Ibid, John Saward, p. 84