Professor Scruton, in your video Why Beauty Matters, about the young composer, Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, dying from tuberculosis at 26, that while writing his Stabat Mater , you said, ” Pergolesi is the Son on the cross.”You did not say, “it is as if he is the Son on the cross.

That seemed like a redemptive moment for you, some grace relieving some of the sadness about all the bad art. You write with clarity and passion about art and religion.

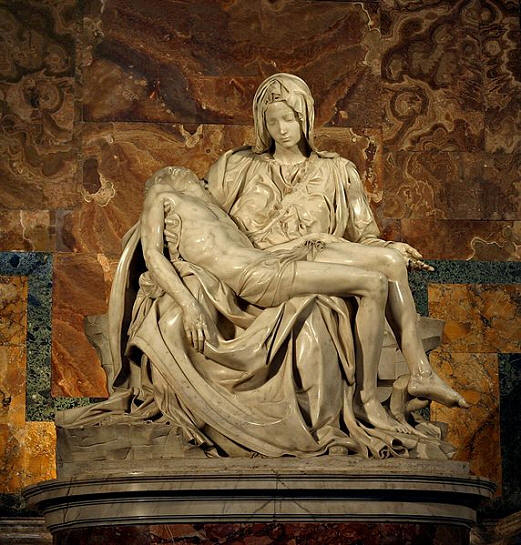

Pieta, detail, Michelangelo, Saint Peter’s Basilica,

It looks as though we both found some hope in art about the suffering Virgin Mother, for you in Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater, and for me it has come in the form of the Pieta. That is where I end my article believing that the way back from the bad art, that you have named as immoral, is a way back through faith.

How did we get from Renaissance Art, faith embodied, to Abstract Art, art without recognizable content, and to Conceptual Art, art which is completely disembodied?

Pieta, Michelangelo, Saint Peter’s Basilica,

As you enter Saint Peter’s Basilica the first chapel on the right is graced by Michelangelo’s marble Pieta. There is always a small crowd, and the silence there rises above the distant din. No-one speaks. Pilgrims are not disappointed, they will remember seeing something that looked like a vision.

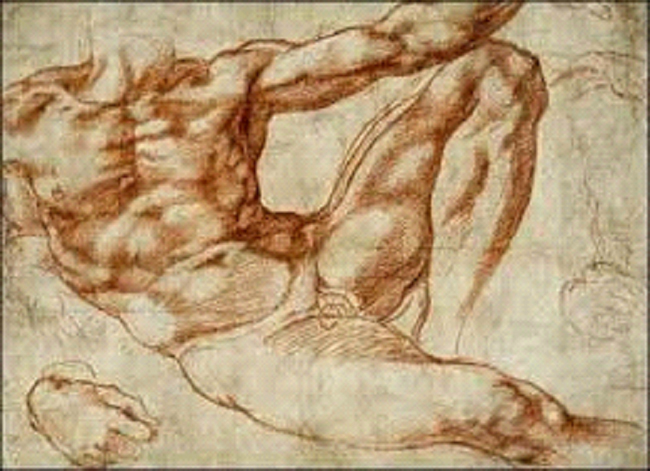

The artist in the Renaissance began training with a master in a guild at age twelve because talent was seen as a gift from God. They learned by copying, as their masters had done before them. Unlike in Modern Art, there was no pressure to always do the newest thing or to shock.

Authority in art went from the guild to the university, from those who do, to the experts who judge. For example, in the

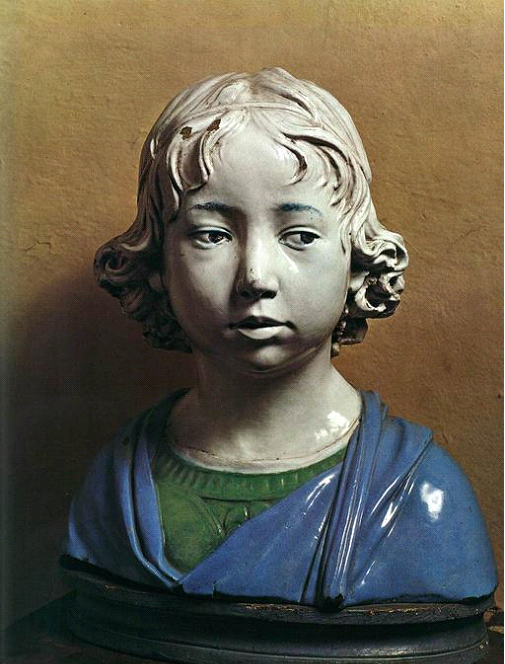

Bust of a Boy, Luca della Robbia, glazed terracotta, 1475, Bargello,

Rene Descartes split body and spirit and I connect that with the split in Late Modern Art between form and content. Form alone, Abstract Art, a painting about paint, is as inane as a poem being solely about the alphabet. Content alone, Conceptual Art, devolved into trite jokes.

Critique of Modernism, Sullivan, 1982, private collection.

And that slit also allowed the taking of the body off of the cross, so the cross became just a symbol, to which you could supply your own meaning. It reminds me of what Flannery O’Connor said at a distinguished literary dinner at which she was too shy to speak, until a woman knowing that O’Connor was Catholic, said, “The Eucharist, what a nice symbol.” To which Flannery responded, “If it’s a symbol, to hell with it.”

The Starry Night, Vincent van Gogh, 1889,

When form and content were partners vying for supremacy in Early Modern Art, exciting things happened. The push and pull of form and content, the interaction, is what gave art such energy. For example in Van Gogh’s painting of the sky we accept the thick globs of paint as sky but we never forget that it is paint.

Study for Adam, Michelangelo, 1510,

The art educational system has failed. “Everyone is an artist, just express yourself.” With no God, the concept of God given ability went away. Billy brings home scribbles from the first grade and they are stuck on the refrigerator and he is patted in the back for the sake of his self-esteem. Billy, that ….. learn how to draw.

Those who critique rule. Those who make, still make, but at the margins of society.

Artists from another time had a significant place in society, Columbia Art Historian James Beck said, “The most remarkable meeting of Renaissance artists ever recorded, and arguably the most extraordinary encounter of its kind in history, occurred on January 25, 1504, (in Florence) when some two dozen painters, sculptors, artisans, and architects were convened to take up the question of the appropriate location for Michelangelo’s all but finished marble David.”-2.

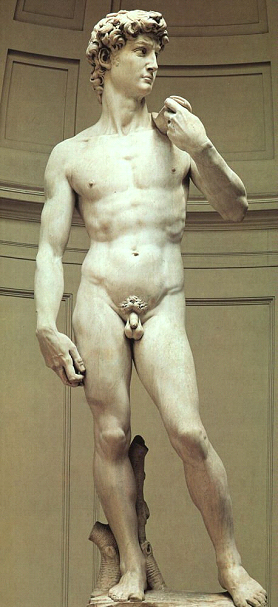

David, Michelangelo, 1504, Accademia,

The group included; the painters, Leonardo da Vinci, Sandro Botticelli, Filippino Lippi, Perugino, Lorenzo di Credi, the architect Guilano da Sangallo, the sculptor, Andrea della Robbia, and more artists and artisans.

A group of two dozen and no theorists, no critics, no politicians, no lawyers, no lobbyists, only those who do, those who make.

From Kenneth Clark’s classic book Civilization from 1969, he says this about the Renaissance, and more specifically about Michelangelo’s David,

David, detail.

” Seen by itself the David’s body might be some unusually taut and vivid work of antiquity; it is only when we look at the head that we are aware of a spiritual force that the ancient world never knew. I suppose that this quality, which I may call heroic, is not part of most people’s idea of civilization. It involves a contempt for convenience and a sacrifice of all those pleasures that contribute to what we call civilized life. It is the enemy of happiness. And yet we recognize that to despise material obstacles, and even to despise the blind forces of fate, is man’s supreme achievement; and since, in the end, civilization depends on man extending his powers of mind and spirit to the utmost, we must reckon the emergence of Michelangelo as one of the great events in the history of western man.” -3.

That gives us an idea of what Christianity brought to the already great antique art.

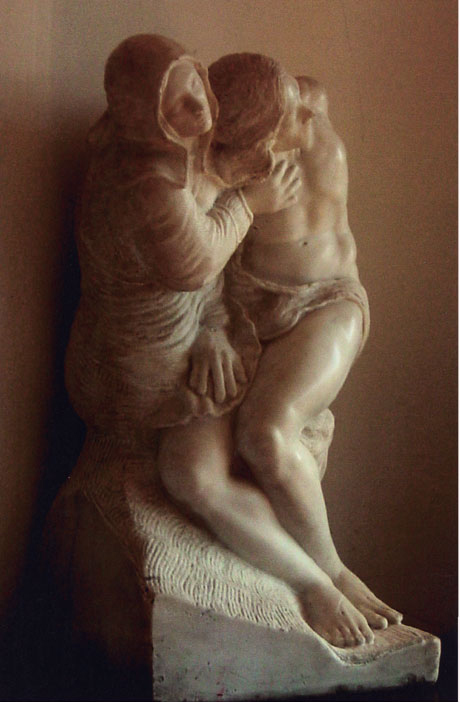

Pieta, Sullivan, Vermont Marble, 1981, Rachel, Sullivan, marble, 1985.

In a similar way we can see how suffering changed, how the isolated suffering in antique art became relational in Christian art and we can see the role that Mary played in the art.

Art Historian Sir Kenneth Clark has much to say about the connections between Antique Art and Renaissance Art. I wrote about him as a Protestant Art Historian who had written with great feeling about the great Catholic Art. My friend Joseph Pearce, the writer, informed me that Sir Kenneth had a death bed conversion to Catholicism.

Kenneth Clark also wrote, from Civilization

“The great achievements of the Catholic Church lay in harmonizing, humanizing, civilizing the deepest impulses of ordinary, ignorant people.

Take the cult of the Virgin. In the early 12th century the Virgin had been the supreme protectress of civilization. She had taught a race of tough and ruthless barbarians the virtues of tenderness and compassion. The great cathedrals of the Middle Ages were her dwelling places upon the earth. In that Renaissance, while remaining the queen of Heaven she became also the human mother in whom everyone could recognize qualities of warmth and love and approachability. Now imagine the feelings of a simple hearted man or woman — a Spanish peasant, an Italian artisan — on hearing that the Northern heretics were insulting the Virgin, desecrating her sanctuaries, pulling down or decapitating her images. He must have felt something deeper than shock and indignation: he must have felt that some part of his whole emotional life was threatened. And he would have been right.” -5

It is not so difficult to imagine that only the “cult of the Virgin” can civilize the barbarism of our age.

Pieta, Sullivan, marble.

Pope Benedict explains how theology changed the classical pagan art that preceded the Renaissance. About the Pieta concept he said,

“The languages into which the Gospel entered when it came to the pagan world did not have such modes of expression. But the image of the pieta, the Mother grieving for her son, became the vivid translation of this word. In her God’s maternal affliction is open to view. In her we can behold it and touch it. She is the compasio of God, displayed in a human being who has let herself be drawn wholly into God’s mystery.” – 6.

He has said that through art, not just from the written word alone, we can understand more about God, in this case, more about the female aspect of his love, “his maternal affliction”, and his “compasio”.

1.. Three Worlds of Michelangelo , James Beck, 1999, p.123-131

3. Civilization, Kenneth Clark, 1969, p. 123.

3. Ibid

4. Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, Mary, The Church at the Source,1997. p. 78.