How Michelangelo Carved Marble Looking Over Michelangelo’s Shoulder As He Carves Marble. Copyright 2025 Cornelius Sullivan

Atlas Slave, Michelangelo, marble, 8′ high, Academia, Florence

Atlas Slave, Michelangelo, marble, 8′ high, Academia, Florence

In Michelangelo’s unfinished carvings there are some completed parts alongside parts still waiting to be found in the block. This can create in the viewer a sense of anticipation, that one is involved with the sculptor in the process of discovery. It is as if you are looking over Michelangelo’s shoulder as he carves.

Michelangelo’s “Non Finito” has been written about in many tangential ways as if it were a peculiarity of the sculptor. In fact it is how he carves.

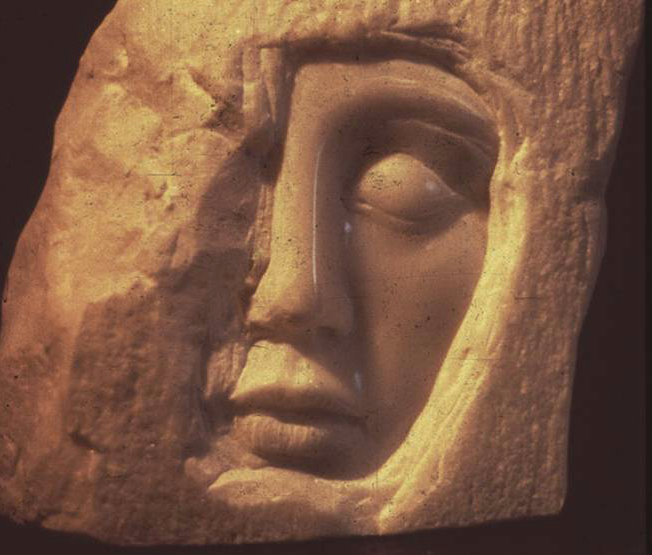

Emerging Face, marble, life size, by the author, private collection Boston.

As a young artist, I picked up a marble boulder from the side of the road near the Vermont Marble Company quarries in Proctor, Vermont. I tried to carve it with a screwdriver. After a while I was able to find some better tools and stop hitting that thumb bone with a carpenter’s hammer. But still, there were no carving teachers. Michelangelo became my only teacher as I studied his unfinished carvings. They presented, like an archaeological record, a physical record of his thinking and of his carving process.

The point chisel, (subia), left deep parallel grooves. I imagined the sculptor wielding a heavy two pound hammer sending sizable marble chips flying as the marble began to yield its hidden beauty. After this, and overlaying this, were fine cross hatched lines left by a toothed chisel (gradina). It traveling around the form and was more caressing and less penetrating than the point.

Michelangelo’s carving method was one of seeing and finishing a part in order to see and then find more hidden in the block of marble. There was a Neo-Platonic element in this method that was consonant with the philosophy that he learned from the poets and philosophers at the table of Lorenzo de Medici.

The process can be called subtractive sculpture, taking away what is not essential. The more usual procedure in sculpture is to build up, often adding on with clay. Michelangelo would not even deign to call this sculpture characterizing it as being akin to painting.

Not all sculptors can carve because carving presupposes the ability to see inside the block of marble. I learned that the great Florentine sculptor was able to aid his vision of what the block contained by finishing some parts of the sculpture prematurely, rather than employing the more normal practice of roughing it out all over as Greek sculptors had done. He was then able to measure from finished parts using his eyes and proceed to find more hidden shapes. Greek sculptors did not have steel tools and their point chisel was made of bronze. They roughed out all over. And they used the point at right angles to the stone and pitting the surface of the stone. That pitting was alright because, after some abrasion of the surface, the marble would be painted.

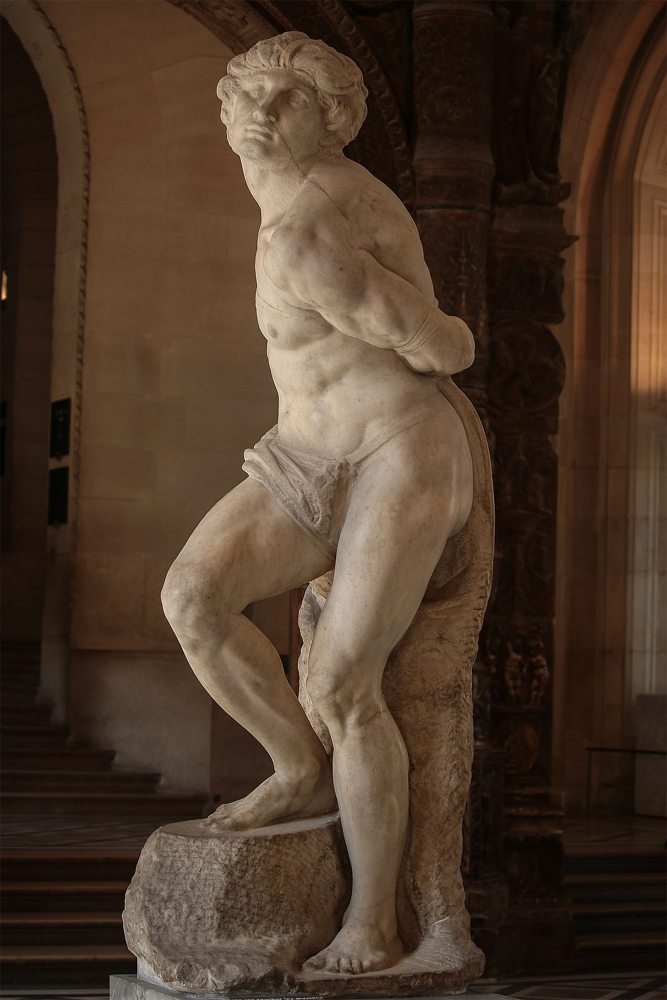

Captives; Atlas, Bearded, Young, and Awakening, Galleria del Academia, Florence.

There are particular works where the uncovering, discovering process is very evident. Form emerges from the marble block in a most dramatic way in his Captives, sometimes called Slaves, that are in the Academia in Florence. And the block is still very much a reality, vying with the figures. Indeed, the figures struggle to free themselves from the block.

The Captive title also alludes to the fact that the figures were meant to symbolize those who were set free from foreign rule by the warrior, liberator Pope, Pope Julius II. The eight- foot high figures were intended to grace Julius’ massive marble tomb that Michelangelo designed for inside of Saint Peter’s Basilica.

With the Captives, he dived into the depth of the block to find the energy of the torso and only then, determined where limbs would be and how big they would be. Everything was measured from the dynamic center.

Some believe that he intended to finished the captives. I am pleased that he did not because of what we can learn from them. There are two finished figures in the Muse de Louvre, one is called the Rebellious Slave and the other the Dying Slave. Michelangelo’s Neoplatonism was mitigated by the fact that he shared with Saint Augustine the unquestionable goodness and beauty of the human body.

Rebellious Slave, Michelangelo, Louvre.

Dying Slave, Michelangelo, Louvre,

Dying Slave, Michelangelo, Louvre,

Different in their “non-finito” than the emerging captives are other carvings left unfinished where we can surmise that he left them that way because of the way they looked. He made an aesthetic judgment. Or, as Michelangelo Scholar William Wallace has suggested, dismissing the conventional wisdom that the sculptor was pulled from job to job by Princes and Popes, he had a such a sense of himself, and his place in history, that he would leave one job to go to a better one.

The two large round Madonnas with Child, the two tondi, are examples of this. They have tool marks from the roughing out point chisel, the as well as extensive modeling with the tooth chisel. I have polished marble because I wanted to see its color and to see how it would take a shine and then regretted the absence of the tool marks because of the fact that the marks take the light and describe form with clarity. And there can be a disorientating sense of loss of the block when traces of it are gone.

Madonna and Child with the Infant Baptist (Taddei Tondo), Royal Academy of Arts, London.

On the bottom of the relief of The Madonna and Child with the Infant Baptist we can see the point chisel gouges. The point was also used to shape the hair of The Baptist. A smaller point made the parallel lines next to the Virgin’s upper arm. Similar marks are on the Christ Child’s hair. The gradina, the toothed chisel, followed the point in rounding the forms. Then a flat chisel would remove tool marks and prepare the surface for abrasion and then a polish. The most finished parts of the sculpture are the Christ Child’s body and the drapery.

Pitti Tondo, Museo Nationale del Bargello, Florence.

This Pitti Tondo clearly shows the progression from point marks in parallel lines, called the mason’s stroke, to the refined tooth chisel and delicate modeling. The finishing of high points in the relief is also evident.

After centuries of sculptors not carving themselves, there appeared in modern times a movement called “ Direct Carvers”. Sculptors wanted contact with the stone themselves and they wanted the finished piece to look like stone. I was influenced by that seemingly honest and direct idea. On one of my first carvings, I made a rough shape of a face on a boulder. Then after a month of looking at what I had done in the modern way, leaving a general shape, my study of Michelangelo asserted itself and prompted me to see inside the block. I peeled back the marble to reveal a face inside, and I left evidence of the process of uncovering. I uncovered it as if breaking through an egg shell. It is called Egghead Muse.

Egghead Muse, detail. Sullivan, marble, life size.

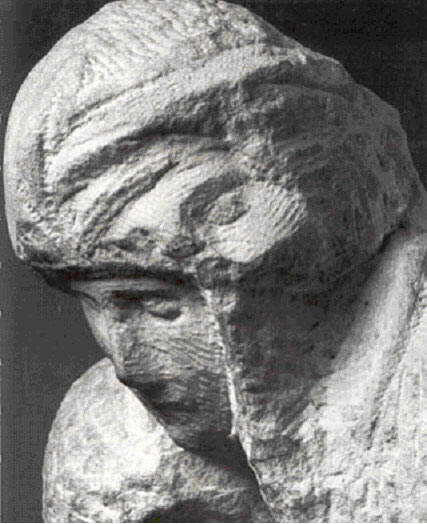

Michelangelo’s last Pieta, Pieta Rondanini, the marble that he was working on six days before he died, presents a dramatic picture of how the sculptor continued to change his marble compositions.

Pieta Rondanini, Sforza Castle in Milan.

There is a tragic and heroic element in the fact that at his advanced age the struggle with marble continued. Gone was the ease and grace of the twenty four year old man who carved the Rome Pieta. As if the Pieta Rondanini were a drawing that could be erased and corrected, he made major changes with the hammer and chisel. It is touching that he ran out of marble and was carving the head of Christ out of the Virgin’s shoulder. It is a very flat unfinished face. There is the remnant on the top of the veil of the Virgin of her face looking in a completely different direction that reveals an earlier version of the work.

These elements show us how he thinks, he continues to draw, he trusts his eyes. This separates him from other sculptors, even Gian Lorenzo Bernini the master of flying marble drapery. It was necessary for Bernini to follow his models exactly. For Michelangelo, it is a dialogue, it becomes like combat, about discovery and change. It is interesting that Raphael painted a portrait of Michelangelo in his School of Athens, in the Papal Apartment of Pope JuliusII, as Heraclitus, the Greek philosopher who said, “The only thing constant is change.“

Pieta Rondanini, detail.

On the Rondanini there has always been a mystery about the large arm separated from the figures. It is connected with a small tab of marble. Its scale is much bigger. It must have been part of an earlier, larger Christ figure. Many bizarre speculations have been written about why the arm is there. I wanted to know why. I knew that I had to see the back of the sculpture. When I taught some drawing classes at Harvard University, Graduate School of Design, I used to have long conversations with one of the most renowned Michelangelo scholars in the world, Professor John Shearman. He told me that he also had to see the back of a marble, the Moses in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli, in Rome. He went over the ropes and was grabbed by the guards. They let John go because he was a suave British gentleman and he spoke perfect Italian. I said, “Professor Shearman, I’m going over the ropes to see what is behind Michelangelo’s last Pieta.”

When I went to Milan in 2005 to see the Pieta Rondanini at the Castello Sforza, there was no need to go over the ropes. The sculpture was in the middle of the room, not in a niche as it had been for so long. Behind the big arm was a copy of it, smaller and attached to the new thin body of the Christ figure. When he was done copying the large arm, the old sculptor would knock it off with one blow of the hammer. This never occurred because of his death.

Michelangelo’s “Non-Finito” refers to leaving his many marble carvings unfinished. There still exists, among experts, considerable debate on the subject. Traditional art historians with their extensive knowledge of peripheral events in the artist’s life will maintain that he was pulled from job to job by patrons, princes, and popes. On the contrary, romantic Modernists insist that he left works unfinished purely for reasons of self- expression.

Renaissance artists were only paid when works were finished. This did not stop Michelangelo from leaving some works unfinished. Contemporary scholar, Professor William Wallace has pointed out that Michelangelo had a sense of his own place in history and that he would always leave one job to go to a better one, to a better opportunity. His sense of himself allowed him to resist external pressures to finish works. Therefore, we can conclude that Michelangelo acted intentionally with regard to the non finito.

Michelangelo’s carvings are dynamic because carving is not just a means to reproduce something conceived by modeling in clay. Carving is a way of thinking, a way of seeing what is not yet there. Each tool leaves a surface rich in suggesting forms. When I carve even the point chisel breaking off large chunks of stone can leave a surface that will suggest, for example, drapery folds. It is similar to Leonardo’s advice to artists to study stains on a wall or on paper and envision a landscape. There is room for inspiration, not like in conceptual art which is a one-way process.

The masters worked with materials and believed in inspiration, a breathing in. Descartes’ disembodied philosophy, I think therefore I am, led to Conceptual art, art that is just an idea disconnected from matter. Carving marble is very collaborative as opposed to an imposition of will upon the material. In fact, if you are determined to impose your will on marble and not work with it and respect it, it will have the last word.

Michelangelo’s unfinished sculptures can tell us a great deal about how he thinks as an artist. His paintings and his Architecture come from the mind of the sculptor. He signed his letters, “Florentine Sculptor”.

.