Caravaggio Speaks to the Modern Age

Cornelius Sullivan

Rome

His paintings were revered and imitated in his own time. He was almost unknown for centuries and in 1951 Italian art historian Roberto Longhi organized an exhibition of his work in Milan and introduced him to the modern age.

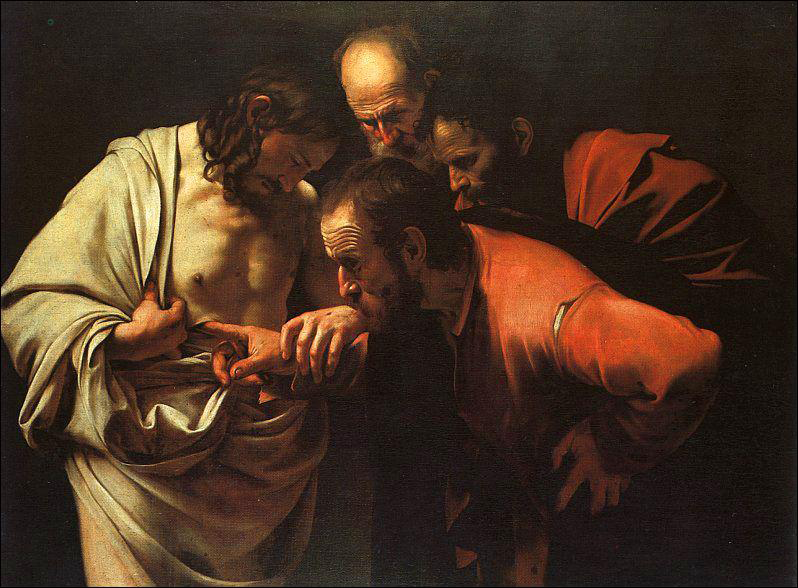

The Incredulity of Saint Thomas, 6602, Sanssouci, Potsdam, Germany.

Looking at the formal elements, how the images are constructed, we see that he was not of his time but centuries ahead in many ways. If the picture plane were a picture window, many of his figures would touch it. They are squashed forward exploding toward us from the shallow space. He eschews Renaissance perspective with its vanishing point receding into a deep well defined space. In fact sometimes his space looks confused and sometimes is not consistent throughout the picture. The reason for this is that he painted his figures from live models posed in the studio. His challenge was that he may have one model one day and at a different time add another figure to the composition. An example of this out of joint space can be seen in the oil of doubting Saint Thomas. When the saint puts his hand in the side of Jesus he looks off in a direction not consonant with what his hand is doing. But with Caravaggio we can never be sure. It may have been intentional. Maybe he wanted to show that Saint Thomas was blind to the truth until he touched.

The figures are close to us, we are drawn into the scene because Thomas’ elbow touches the picture window.

In the Madonna of Loreto the pilgrim’s dirty feet are trust at the viewer at eye level, the soles would touch the window. The dirty feet are a feature that is never lost on art critics with a political agenda who characterize Caravaggio’s art as being for and about unwashed pilgrims.

A case in point is a new biography by Graham-Dixon from 2010. His religious and cultural bias has not allowed him to give a credible portrait of Caravaggio, it’s as if he doesn’t like him. Unlike viewers who accept his paintings on the painter’s own terms, the cognoscenti try to confine, categorize, and qualify him. I was warned in the beginning of the book when the author called post Council of Trent, Counter Reformation spirituality in Caravaggio’s Rome “superstitious”. Then he devoted nearly thirty pages to discrediting Saint Charles Borromeo who was the bishop of Milan saying, “Borromeo did not entirely succeed in his efforts to turn Milan into a model Tridentine police state.” He goes into great detail to chronicle the depraved quality of cavalieri in Rome at this time comparing them to the pure chivalrous knighthood of the time of King Arthur. King Arthur is fiction, we know that Caravaggio used street people as models but it is what he did with them, it is about the art, that’s the compelling story.

Dixon says that Caravaggio’s art came from the overly theatrical terra cotta religious folk sculpture of Lombardy. Nothing could be further from the truth. Caravaggio was a pure painter influenced by Gorgione and the Venetian colorists. Sculptural language and the way that sculpture commands real space is the antithesis of the way this master paints.

Helen Langdon’s Biography, Caravaggio: A Life, 2000, is the classic, often quoted biography. Francine Prose is a writer and creative person, rather than an art historian, she understands the artist in a way that Graham-Dixon does not. Her short biography is called, Caravaggio, Painter of Miracles, 2010. Dixon would never use the word miracle.

Madonna of Loreto, 1606, San Agustino, Rome.

Another feature of Caravaggio’s art is his consistent attention to composition in a modernist way with control of value and color. If you look at value alone in a black and white reproduction of one of his paintings you can not miss the precise puzzle like structure. Often he will hang or suspend a drape over a group of figures. It is a made up compositional devise. The abstract design of the cloth complements and sometimes echoes the movement of the figures. The large drape above The Death of the Virgin is an example where it takes up almost the top half of the painting.

Like an abstract painter he is cognizant of abstract structure and then he gives us more. Abstract artists would have us believe that all that counts is a personal idiosyncratic design that oozes out from their inner self onto the canvas. How can we accept that when the masters give us better design along with representation and all the layers of meaning that come with that? More is better.

Death of the Virgin, 1606, Louvre, Paris.

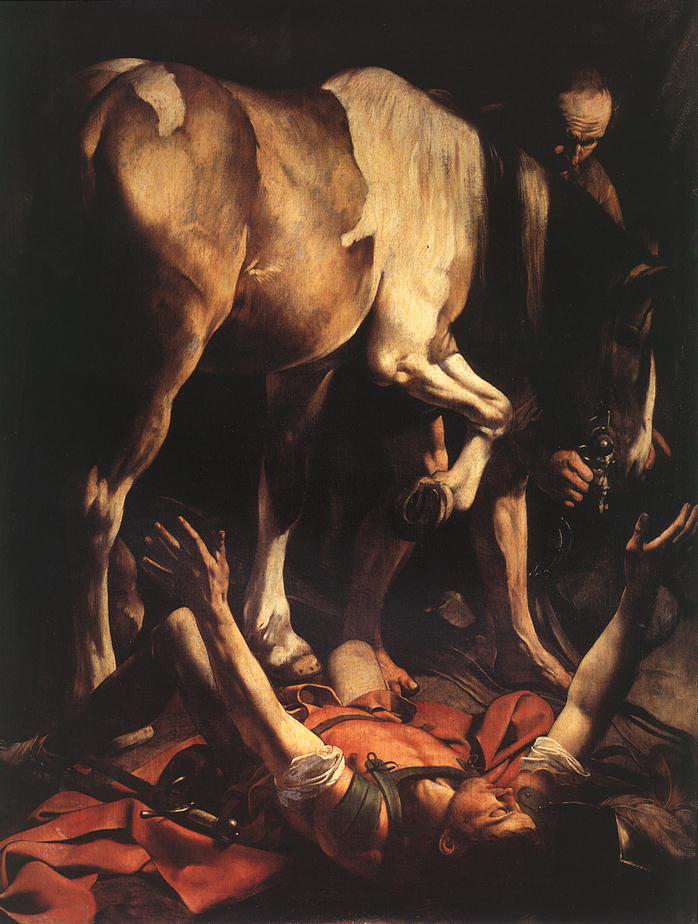

His color is not only local color, it often has harmonies of adjacent hues as in the oranges, reds and greens of Saint Paul.

Conversion on the Way to Damascus, 1601, Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome.

The Baroque master’s paintings connect with ease to the contemporary mind because we get the meaning all at once. The master story teller gives us stopped action and a telling ensemble of gestures. From the Renaissance and from his time artists were restricted by agendas to signify the status of a character and often their visual creativity might be crimped by a literal narrative. This does not happen with Caravaggio. When he paints, the visual essences take priority. He invents his own special way to embody the narrative. In the Conversion on the Way to Damascus the story and the visual impression have become one.

His paint is always beautiful. His lights are thick and opaque. Often there are wide expanses of flesh or cloth. His darks are deep and mysterious.

And finally we are intrigued today by his biography. Helen Langdon sums it up well in the introduction to her biography.

“The most famous painter in Italy, and celebrated throughout Europe, he was also feared as a difficult and strange personality. He flaunted his originality, and mocked authority; he was fearless and belligerent, and in 1606 he killed a man, and spent his last years in exile. His greatest gift was for empathy, for making religious narrative new and vivid, and it is through this, and through his compelling personality, that he speaks so directly to the modern age.”