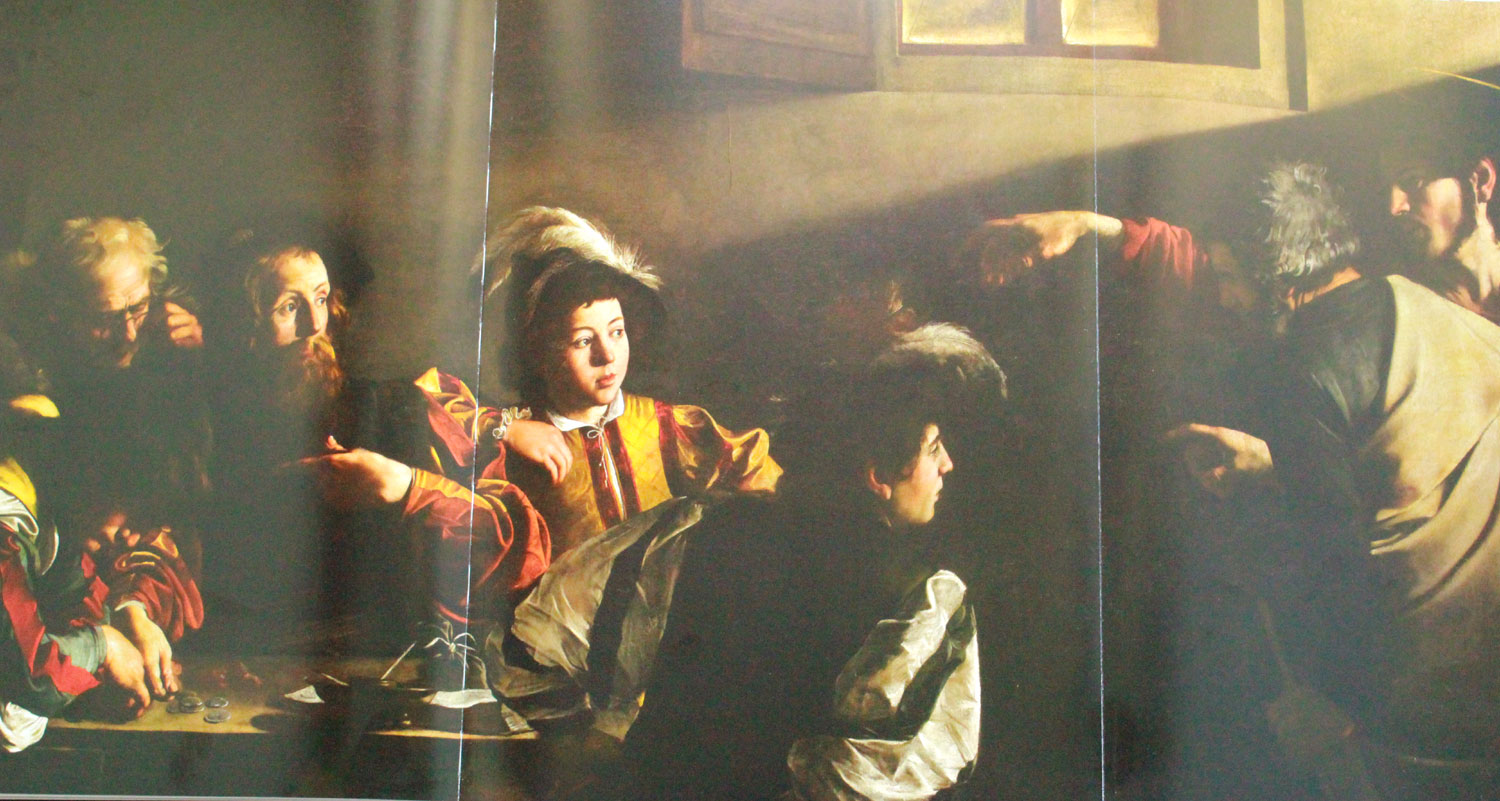

Who is Saint Matthew for Caravaggio?

Calling of Saint Matthew, Eye Contact detail.

Calling of Saint Matthew, San Luigi dei Francesi,

Cornelius Sullivan

Is the boy in darkness at the end of the table really Saint Matthew? This is not a new idea, it has been around for some time, but it has never gained wide acceptance because it is counter intuitive.

Sandro Magister posted art historian Sara Magister’s ideas proposing a different Saint Matthew on www.chiesa, ideas that were presented on the Italian Bishops TV2000 a few weeks ago.

I view Sara Magister’s speculation as an exercise in creative writing. Caravaggio tells the whole story in stopped time as he did in many of his other paintings. Art historian Elizabeth Lev in her Zenit article response to Magister’s claim said that “Caravaggio’s most important characteristic, besides his dramatic use of light, was his penchant for capturing the culminating instant on canvas.”

Caravaggio is a master story teller and we know at first glance what he is saying.

I have previously written about the simultaneity in the Calling of Saint Matthew. To say that the young man would later look up is not something that Caravaggio would leave for us to guess. His stories are complete. He is not an abstract artist where the viewer gets to supply his own meaning. The painting is “The Calling of Saint Matthew”. Trying to decide who is giving money to who by looking at fingers is like a shell game that does not lead anywhere. There is no hidden meaning, no “Caravaggio Code”, no parable about money lending or gambling. Pope Benedict’s homily that has been linked to the painting was no doubt about the essence of the gospel, about the tax collector who was chosen, he who was not a well loved member of his community because he collected for the Romans and was allowed to take a cut for himself. There is no reason to think that Caravaggio would rewrite the gospel.

The gospel narrative could not be more concise. “Jesus saw a man named Matthew at his seat in the custom house, and said to him, ‘Follow me’, Matthew rose and followed him.” Inventing subplots about money lenders is to remake Caravaggio in our image to be somebody that he was not. He was an orthodox Counter Reformation Catholic artist who followed the precepts of the Council of Trent to make religious paintings with clear unambiguous meanings. It is a mistake to over think Caravaggio.

Putting a new meaning onto the painting would necessitate that the gospel be rewritten something like; “Jesus saw a man named Matthew, and said to him, ‘Follow me’. Matthew did not hear him and did not respond.”

Since the story is the calling, the gesture of the man with the beard “Who me?” is appropriate and does not require any further explanation. The boy looks too young to be a tax collector. If you take away all the other characters and only Jesus and the man with the beard remain, the story is still complete. If it is only Jesus pointing to the boy with his head down, there is no story of calling and hearing the call. The gospel account does include the hearing.

In all of Caravaggio’s other paintings we can easily identify the main character. That main character is never part of the crowd described solely with a touch of light on the nose and chin. The painter always gives us more, often employing pose and gesture.

The composition is a boomerang. The circle of figures around the table slings the gesture back to Jesus. The man pointing to himself accelerates that movement. And the feathers on hats point the direction of the movement going from Jesus on the far side of the table, coming around the curve at the end of the table, and returning on the near side accentuated by the lean of the figure closest to Jesus and Saint Peter.

In Dr. Magister’s response to Dr. Lev’s critique she says that Jesus is aligned with the center of the rectangular table and looks strait at the boy at the center of the other end of the table. In fact, Jesus is lined up with the far edge of the table and indeed does look strait ahead at the man with the beard pointing to himself. Saint Peter is by the middle of the table. There is even eye contact between Jesus and the man with the beard. In the detail photograph the lower lid of the eye of Jesus shows where he is looking.

To say that the boy would look up after this moment is a proposition contrary to the way that Caravaggio paints. He gets all the action at once. He never paints a “before”. Sometimes he paints an “after” as in the case of David holding the head of Goliath in the painting in Galleria Borghese.

Michelangelo’s David is in a before pose, a Renaissance timeless classical repose. Bernini’s Baroque David is in the act of slinging. As a Baroque artist Caravaggio also depicts movement and the moment.

In Caravaggio’s The Raising of Lazarus, Jesus is not shown calling “Lazarus come out” before the action. The simultaneity of all the action is obvious. The pointing, the calling, the raising, the pulling up, is all happening at once and Lazarus is already up as Jesus points. The artist does not require that we use our imaginations to complete the story.

Professor Lev with insight uses the contextual features of art history; public, precedent, and practice to identify Saint Matthew. Art history is about the study of style. Christian art history is about the study of meaning.

We have grown up with abstract art and we know that in art, truth is relative, why can’t we make up our own interpretations of the story? You can, but don’t for a minute believe that Caravaggio intended to make a puzzle or that he intended to not have the last word. He would be surprised by viewers providing their own superfluous meanings.

He told Gospel and Old Testament stories with power and also with clarity. Art Historian Kenneth Clark said that the Calling of Saint Matthew changed the history of painting. It did establish how religious paintings would be made for the following centuries.

If you have any doubts about meaning in a Caravaggio painting, follow the light. Sebastian Schutes does just that in the classic Taschen monograph on Caravaggio, “the light falls with full intensity upon Matthew, who in a moment- illuminated by divine illumination- will rise in order to follow unreservedly his calling to be a disciple. Thus the two brightly lit youths at the top end of the table have also turned toward Christ, while the two figures in shadow at the far end, entirely preoccupied with the financial matters at hand, are still completely unaware of the divine message. The process of conversion and the impact of the divine are illustrated metaphorically by light and shade.” And biographer Helen Langdon follows the light and says, “The light falls on Matthew alone, while the other figures remain nonchalant. The youth at the end of the table, his head in shadow, his fingers lingering on the coins, suggests unredeemed humanity, dwelling in darkness, and perhaps carries overtones of the story of the rich young man who could not forsake all and follow Christ.”

There is no need for an expert to explain what a Caravaggio painting is about. As a story teller he does accomplish what he intends. Is this the only case where Caravaggio tried to tell us a different story, but just did not give us enough evidence to believe it? That is not likely. As seen in situ in the Contarelli Chapel it looks like the gospel story, Jesus calls the bearded man and the man reacts.