Michelangelo Attacked the Marble Block to Find Moses

Cornelius Sullivan

Although Michelangelo spent most of his creative life in

There are three masterpieces by the same artist in three different mediums at the

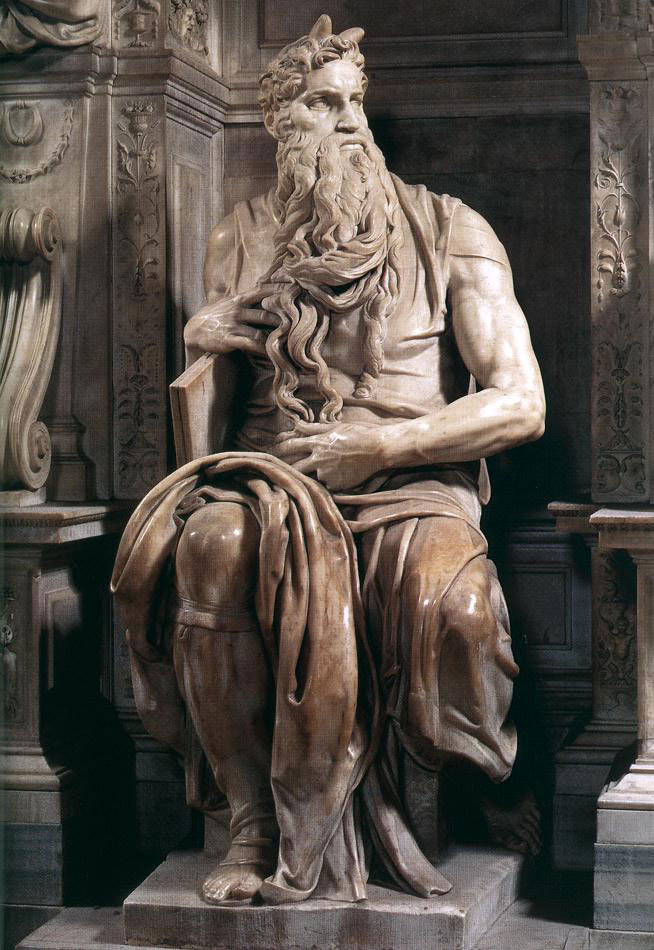

Moses, Tomb of Pope Julius II, San Pietro in Vincoli.

Pilgrims for Art make their way to the

Moses is part of the tomb of Pope Julius II in the church. Moses is one of the forty large figures in Michelangelo’s first design for the tomb. Pope Julius built the new

Michelangelo biographers all give a chapter to the “tragedy of the tomb”. They propose that it was a tragedy because the obligation to complete it haunted the sculptor for many decades. He was contractually responsible to the heirs of Pope Julius but was most often working for successive popes on other projects that he wanted to do more. Irving Stone’s historical biography of Michelangelo and the movie, “The Agony and the Ecstasy” were about the interaction of the sculptor and Pope Julius centered around the Sistine Chapel ceiling. Had it been about the tomb, it could have been called just “The Agony”.

The grand scale of the basilica at the

Julius’ tomb in Saint Peter in Chains is a small version of the grand plan. Along with Moses Michelangelo carved Rachel and Leah, Old Testament figures symbolizing the active and contemplative life respectively. It has been recently discovered that the master also carved the head of the portrait of Pope Julius.

Moses was carved completely by the master and he polished every surface. The prophet has the clearly described strong arms of the forty year old stone carver. The horns on his head come from a mistranslation from the Hebrew to the Latin Vulgate of a term meaning radiant. The Greek Septuagint translated the verse as “Moses knew not that the appearance of the skin of his face was glorified.” One could not see the face of God and live. But God “…spoke unto Moses face to face, as a man speaketh unto his friend.” Exodus 33:11.

Moses seated is nearly eight feet tall. He has a monumental presence apart from sheer size by virtue of his personality.

How could the sculptor make a dynamic sculptural composition out of a seated figure? Michelangelo makes up shapes that have only a slight reference to real materials as for example cloth or hair. The reason for these shapes is primarily sculptural. Moses turns his head to his left and the flow of his beard takes the viewer’s eye cascading down to his beard entwined hand resting on the tablets of the law. The three dimensional definition of the beard is more like an architectural feature than a representation of hair. It has the rich incised detail of a Corinthian capital. That movement down is completed by a large pleated envelope shape between the legs of the figure, the robe folded over his leg.

Carving for Michelangelo is always about attacking the marble block. What is left is left only because it did not impede his thrust inward to find the central structure of the figure. With the Moses he goes deeply into the block and there are unusual shapes enhancing the figure so it appears that he lives.

For Michelangelo carving is primal. It’s him and the block and the dialogue of what he can get out of the block, or find in the block, by pushing the material to its extreme limits.

Risen Christ, marble, Santa Maria Sopra Minerva,

Another larger than life size marble figure is The Risen Christ in Santa Maria Sopra Minerva near the Pantheon. It has a compact contrapposto characteristic of Michelangelo who often took classical poses and made them more extreme and consequently more expressive. The figure is triumphant with his cross and has a revolutionary Apollo-Christ head. Although its inspiration is classical it has the Renaissance feature of possessing one principal view as if it originated as a relief. This also comes from Michelangelo’s carving method of searching in the block for the figure by uncovering and finishing some parts so that they can lead to the location and shape of other parts. Aside from the very beginning, he does not measure from a small model, he measures proportion from what he has already carved. It is as if he is always drawing and he trusts his eyes to measure. This makes the process somewhat unpredictable and always dynamic.

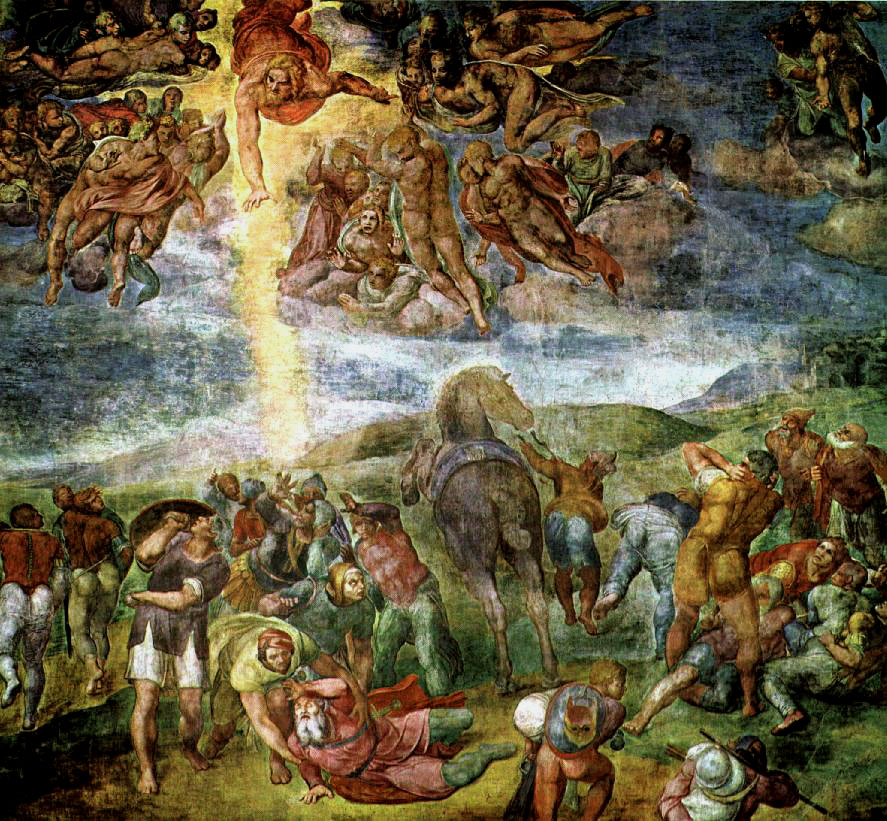

The Pauline Chapel, in the

Conversion of Saint Paul, Michelangelo, fresco, Pauline Chapel,